This week was not terribly interesting since I was just messing around with particle systems.

I attempted to install Unity 5 on one of the lab computers since it provides a lot of nice graphical features such as physically based rendering and HDR. Unity 5 requires a license since it’s in beta at the moment and licenses cost about $70 a month so I was hoping that the license the school has applied to the 4.4 and 4.6 versions of Unity would automatically apply to 5. Nope. I even went and tracked down the college’s key to put it in manually, but the setup told me that the key was not usable for the new version of Unity. The license name says it’s for 4.x so I guess we’re out of luck until the school decides to go and spend $112,500 for Unity licenses at each lab seat since it follows that pricing model where you need to buy a full copy for each computer; no exceptions, no bulk licensing.

I think that starting next year the programming and design-related classes should switch from teaching and requiring Unity3D to Unreal Engine 4. Here’s why I think so:

UE4 is free for all students

Unreal engine 4 normally costs $20 a month for a subscription. This is far cheaper than Unity Pro’s $70 a month. Sure, Unity has a free version, but it’s not nearly as full-featured as Pro. Just to list a few major features Unity 4 free does not support; it does not have any post-process effects (including, but not limited to SSAO, bloom, DOF, HDR, and tonemapping), profiler, custom render targets (for stuff like security cameras), external DLL support (can’t link to C/C++ libraries for stuff like custom input devices), or GPU skinning.

The school supplies licenses for lab computers, but It’s much more convenient to be able to develop on home computer rather than needing to do all development in labs.

UE4 is free for students through GitHub’s student developer pack. It is fully-featured, and can be installed on any number of computers.

UE4 uses C++

Most of the industry uses C++ to develop for console and PC titles whereas Unity uses C# running on a strange subset of .NET 2.0 using mono. To put that in perspective Microsoft is currently on version 4.5 of the .NET framework and 2.0 was released in 2005 – before Windows Vista was released. There’s a ton of features the current .NET 2.0 subset lacks and it especially falls behind when it comes to its garbage collector. C# is a language with managed memory. This has the benefit that you don’t need to worry about freeing allocated memory most of the time, as it will be deleted automatically when it falls out of scope. In order to do this, memory managed languages normally have a garbage collector which goes through the application’s memory as it is running to find unreferenced memory and free it. The version of .NET that Unity uses has a rather inefficient garbage collector which is known to cause periodic stutters in the frame rate of games when it kicks in and frees unused memory.

While it seems that they are moving away from mono, it looks like they will take another year at least to transition out of it.

Unreal Engine 3 used UnrealScript which, according to seniors of previous years who used it, was hard to work with. Unreal Engine 4 uses straight C++ for programming and has a node-based visual scripting language called Blueprint. Using C++ makes it a lot easier to pick up quickly since many of the other classes teach C++. Unreal Engine 4 is tied in with Visual Studio 2013 which all people in the game programming major should be familiar with.

Art classes are already using it

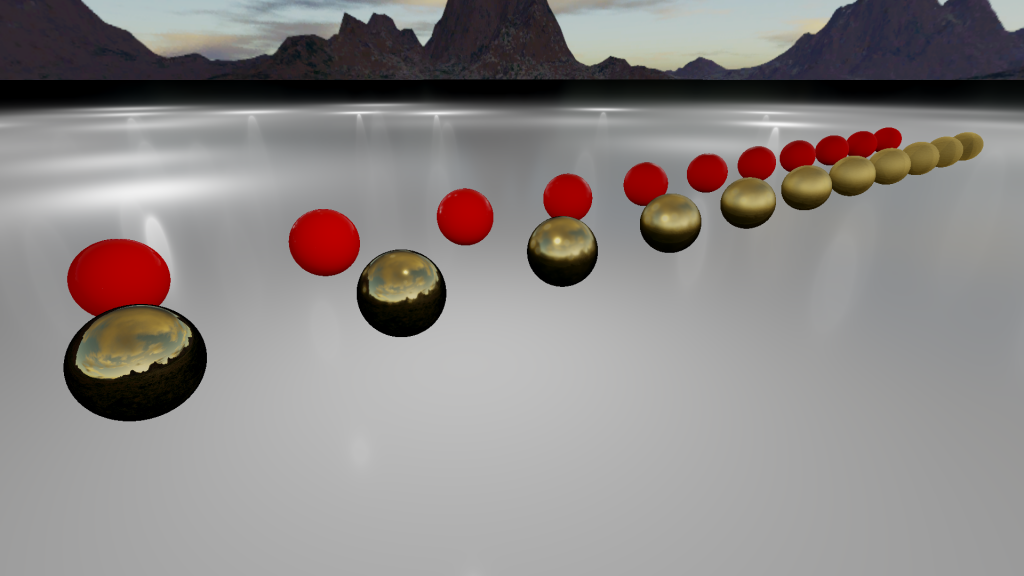

I constantly hear my friends in the game art major talk about how they prefer Unreal Engine 4 far more than Unity. I can see why they do. First of all Unreal Engine 4 uses a physically based shading(PBS) model. Physically based shading allows for much more physically accurate approximations how light actually works when it hits a surface. With UE4′s model you are able to get much more realistic metals and dielectrics that don’t need to be tuned for each environment they are placed in.

The game industry is quickly moving towards PBS because of it’s ability to make one asset that looks correct in all environments. Unity 5 also has PBS, but from what I’ve read, it’s a little more of an approximation than Unreal’s shading model in order to get some performance at the cost of visual fidelity.

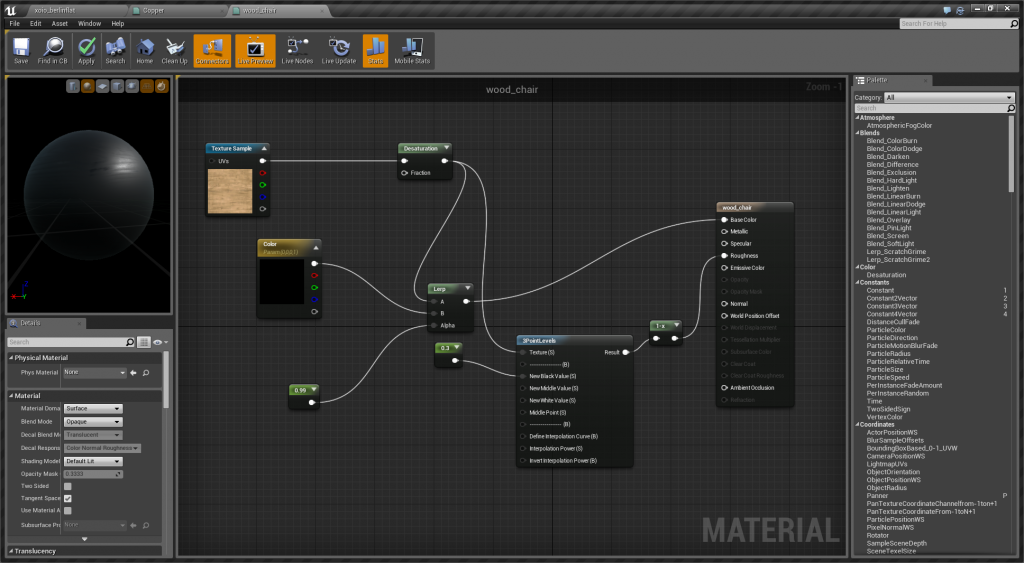

Unreal Engine 4 has a node-based shader editor. This allows artists to make complicated materials for objects without needing to code at all. Unity has plugins that give this kind of functionality, but they do not have as many features and cost money ($90 for the most popular one).

UE4 also has very advanced lightmapping capabilities if you’re willing to give it a few hours to bake the light maps. If you combine this with the material system and post-processing effects it is possible to make some amazing stuff.

At least for the artists, I know that moving to UE4 for senior production would be the best way to rekindle interest in the senior production classes. At the moment it’s more of a situation where production games could potentially hurt their portfolio from an art standpoint since they are using UE4 in their portfolio classes.

C++ to blueprint workflow

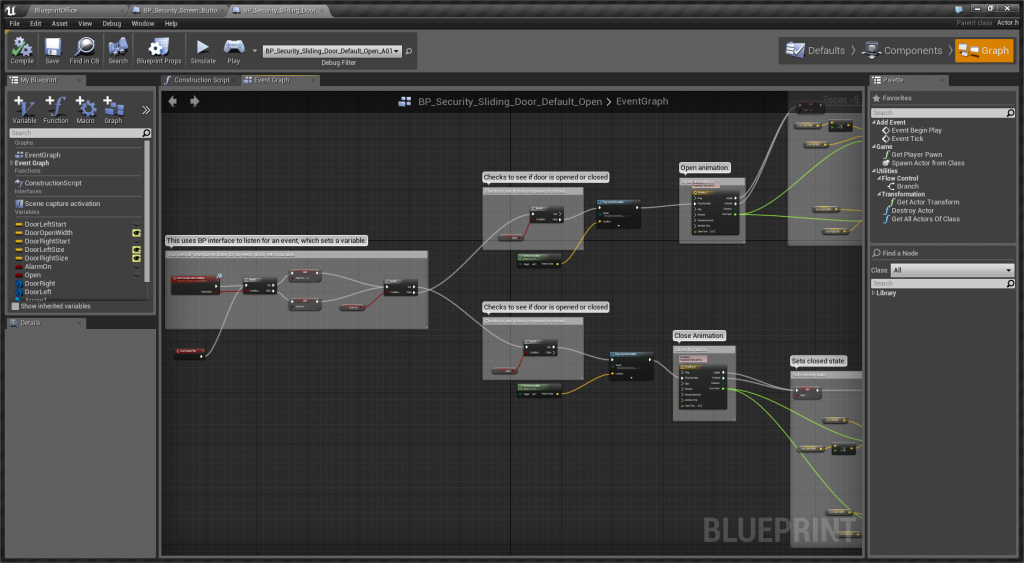

Unreal Engine 4 has a new node-based visual scripting system called Blueprint. This allows quick and easy implementation of game logic. I was kind of adamant about using it because at first it seemed like I wouldn’t be able to do much with it. I was surprised to find that there’s not much you can’t do in blueprints that you can in C++. It’s fully-featured enough to make entire games using blueprints. The only limitations are that many of the under-the-hood features of UE4 such as directly accessing the PhysX API can only be accessed by C++.

This small blueprint does a lot of stuff. It receives input from a button, plays a sound, and animates opening doors.

Blueprints allow an awesome workflow that allows programmers to make more complicated game logic in C++ and expose it to designers in blueprints who can then implement logic of their own on top of the C++ code and tweak variables exposed by the programmer.

You get access to the engine’s source

As long as you have a subscription to UE4, you get access to the entirety of the engine’s source code through Epic’s GitHub account. This is vastly helpful when you’re debugging things. It’s also interesting to just read through the source to get an idea of how large engines are put together.

Because of this it’s possible for people to see exactly what Epic is implementing in the engine at any given moment, and even more importantly, the community can fix bugs and implement new features then commit them back to the engine for everyone else to use.

Iteration time

Epic has been iterating on the engine much more rapidly than Unity. New features are added constantly, and it’s always awesome to read the patch notes for a month to see how much they have added.

Developer grants

Epic recently announced Unreal Dev Grants which is a program where they will give between $5,000 and $50,000 to individuals or teams making things in UE4. At the moment they are drawing from a pool of $5,000,000 for these grants. There are no requirements other than the project needs to use UE4 and demonstrate the power of the engine. Epic announces who gets the grants so it’s also free publicity for the games and they welcome students and educators to make use of the program.

Much more

There’s a ton of other stuff UE4 gives that would take a while to list in detail (dedicated particle editor and GPU particles, automatically synced networking, dynamic navmesh generation for pathfinding, behavior trees for AI, dedicated animation and skinning editor, cloth simulation, dedicated cutscene editor, splines, etc.).

I worked with UE4 last semester and was able to get fully familiar with it after two weeks because of Epic’s extensive video tutorial series on how to use UE4.

I really liked working with it, and once I got the hang of it, UE4 was much easier to work with than Unity in pretty much all aspects.